Debating the Dandy: Reflections on Vogue’s May/Met Issue shot by Malick Bodian

Guest post by Chloé Hirschman

Please consider supporting Shade Art Review with a subscription. As a reader-supported publication, I share 50% of all subscription income directly with my contributors.

If you're unable to subscribe for the 83p weekly, please like and share this work to help it reach a wider audience. Shade Art Review takes hours of dedication to produce, and while we deeply appreciate your emails of support, financial contributions make it possible for us to continue publishing. Your subscription makes a real difference in sustaining independent art writing and fairly compensating contributors.

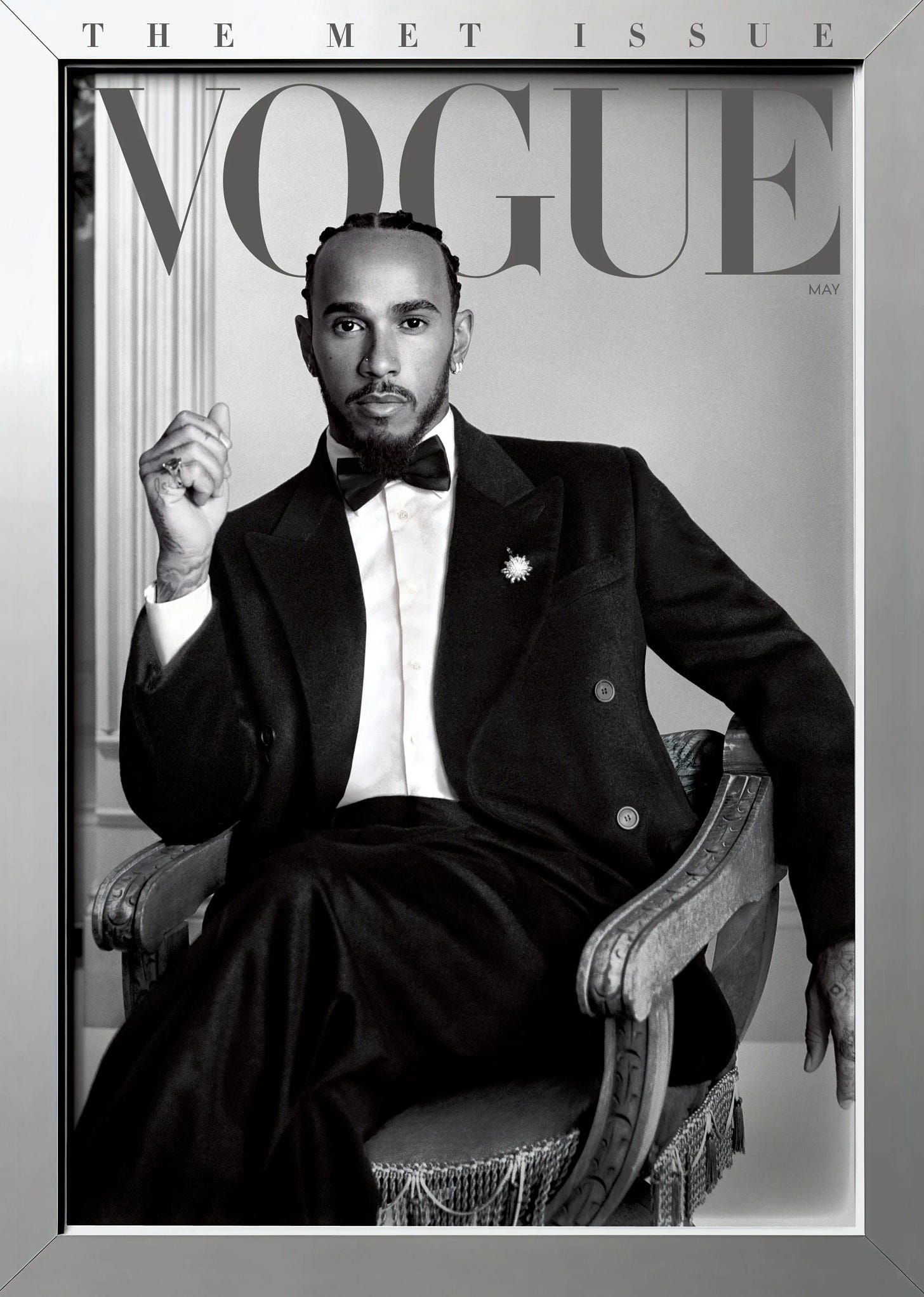

Vogue's May 2025 Met Issue sparked conversations far beyond fashion circles. Malick Bodian's photography, which referenced Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé, raised questions about cultural exchange and representation in mainstream media.

In today's post, Chloé Hirschman argues that fashion photography is a site of cultural and political meaning. She explores how contemporary photographers like Bodian can honour Black artistic lineages within commercial spaces.

Enjoy! Lou x.

Vogue magazine might seem like an unlikely subject for Shade Art Review. After all, Lou’s publication is known for its thoughtful reflections on exhibitions, counter-critical discussions about the art industry and deep dives into what truly matters in contemporary art. And here I am, pitching Vogue.

But, hear me out! The culture industry would not exist without the masses, and the masses are not going to museums. Or contemporary galleries. Or Frieze Art Fair (except maybe on Sunday for the vibes, if they can afford the ticket). And so, magazines - like record sleeves once did - provide a glimpse of art to many who might not be accessing it elsewhere. The beauty they broadcast is political; it shapes popular consciousness. And although Vogue readership is largely connected to industry professionals, the images they diffuse to their 51 million Instagram followers are not reserved solely for those in the know. They’re for everyone. With a smartphone.

The Met Issue embodies the complicated nature of the culture industry. Meaningful in its fusion of different forms of art and in its accessibility, questionable in its ideology. Adorno stated in 1975 (although I rather imagine him hissing in contempt) that the industry “transfers the profit motive naked on cultural forms”. And so it is from this point I would like to dive into the work of photographer Malick Bodian in examining his shoot for Vogue’s Met Issue, May 2025.

For anybody who doesn’t follow, the Met Gala’s theme this year was based on their Spring 2025 exhibition “Superfine: Tailoring Black Style”. The exhibition draws from the 2009 book Slaves to Fashion: Black Dandyism and the Styling of Black Diasporic Identity by the Professor of Africana Studies at Barnard College, Monica Miller. Bodian’s fashion story for Vogue references this, and his brief was to “do a story on dandyism”, a sartorial style which served as a defiant reclamation of Black identity.

Shooting Black models originally from Senegal, South Sudan and Guinea-Bissau, Bodian references the founding fathers of African portraiture, Sidibé and Keïta. Bodian’s models stand in a studio resembling Keita’s own, with the same patterned floor and vintage props on which a model proudly, yet languidly, rests a foot.

This shoot might make some uncomfortable. The referencing of Sidibé and Keïta in this context could be interpreted as tacky marketing - where African visual languages are transmuted into commodified assets when filtered through mainstream, mass-media channels. This brings up some interesting dynamics. Here, I think it is important to consider the work of the artists referenced. Both Sidibé and Keïta are commercial photographers.

“Generally speaking, for an African photographer, getting paid is the name of the game. We don't just pick up a camera for the pure pleasure of it, you know.” Sidibé was quoted in conversation with Michelle Luminaire, 2001. “It wasn't the love of the camera that first drew Africans to photography, it was the promise of financial gain and respectable employment.” he goes on to explain.

Thus for Sidibé there is nothing wrong with the transmutation of African visual languages into commodified assets. Another issue might be if profit is one sided, or gained at the expense of agency. The anger of some of Sidibé’s subjects at the unauthorised use of their image has been documented, for they did not expect their private portraits to be blown up on gallery walls in Paris. But that’s another conversation for another time. At least in Bodian’s shoot, the subjects were willing, consenting professionals and credited.

Yet regardless of controversies, these artists were fundamental to changing ideas of Black Beauty in fashion, and for this reason it seems particularly apt for Bodian to reference their work. Bodian’s shoot captures an elegance, a deliberate “aesthetic of blackness” that is published by Vogue precisely because it is marketable. If people (and by people I mean the millions of readers, for this is the focus of mass-media) were not interested, it would not exist. And perhaps this means that the aesthetic exists within an established framework focussed on profits. But it also means that people desire to engage with this aesthetic, that the Western framework has been navigated to portray non-Western imaginings of beauty, captured by those who embody it.

Bodian began his career on the other side of the lens. He is both a model and a photographer, and perhaps this positionality contributes to the angle of his work. In this issue, his subjects stand out powerfully - perfectly lit, framed, delicately reflecting tonal nuances of dark skin in a way that doesn’t flatten or distort them. Bodian pays careful attention to every detail, evidenced by the specific, dancer-like poise of the models’ fingers, to the shadows which lightly brush but never obscure their faces as they stare directly at the camera, calmly self-assured, eyes brightly illuminated. The subjects wear the fashion, not the other way around. There is a strength and a dignity that radiates outwards, and a mise-en-scène that is critically considered to portray this. If photography, like fashion, is a tool to construct identity and tell stories, it is a tool Bodian knows inside and out.

This tool can also challenge stereotypes and reshape narratives. When the daguerreotype process arrived in the United States in 1839, it coincided with the rise of blackface minstrel shows that perpetuated dehumanising caricatures of Black people. Photography became a powerful medium for creating dignified counter-representations of Black American life, offering authentic portrayals that stood in direct opposition to these racist stereotypes. Later, and on a different continent, photography by Sidibé and Keïta in newly independent Mali showed an alternative identity to the colonial portrayals of the time. And it is my view that Bodian’s photography, in one of the world’s most prestigious fashion publications, is part of this trajectory. It is showing a notion of Black beauty that draws on a long lineage of African visual history. It has its roots in history and it is claiming space in the contemporary.

I do not believe this cultural exchange is simply a masquerade of progress. Bodian navigates an established institutional framework through his deliberate choices, specific references, and in the successful execution of his vision (which includes a multi-racial artistic team). If cultural exchange involves a coalescence of backgrounds and ideas, Bodian’s fashion story is emblematic of this. The fact that its dissemination is not only through print but also digital media, a medium which enhances connection and renders borders less distinct, means that his work is seen by more people, in widely dispersed settings. His aesthetic of beauty reaches millions. This feels important.

Dandyism was a strategic negotiation of racist tropes, and this Vogue issue reminds us that beauty, especially in relation to the canvas of Black bodies, is political, cultural, and relevant. Bodian executes such dynamics in a way that is at once delicate and striking. Viewing beauty in the context of a fashion editorial, via my smartphone, doesn’t make its meaning any smaller.

His photographs challenge, celebrate and...make me want the clothing. In doing so, they prove that the political and the commercial need not be mutually exclusive; sometimes, they can be mutually transformative.

Chloé Hirschman is a South African model / actress / writer / art enthusiast (that’s a lot of slashes) who is currently studying towards an MA at SOAS in Global Media and Digital Cultures.