Dennis Morris at the Photographers' Gallery, London.

From front page news at 11 to Island Records art director at 19, 'Music + Life' shows that the photographer is more than Marley and punk shots.

I popped into the Photographers' Gallery this morning - wasn't planning a free, bonus post, but came away more inspired than I had anticipated. Written on the train home, bear with any errors

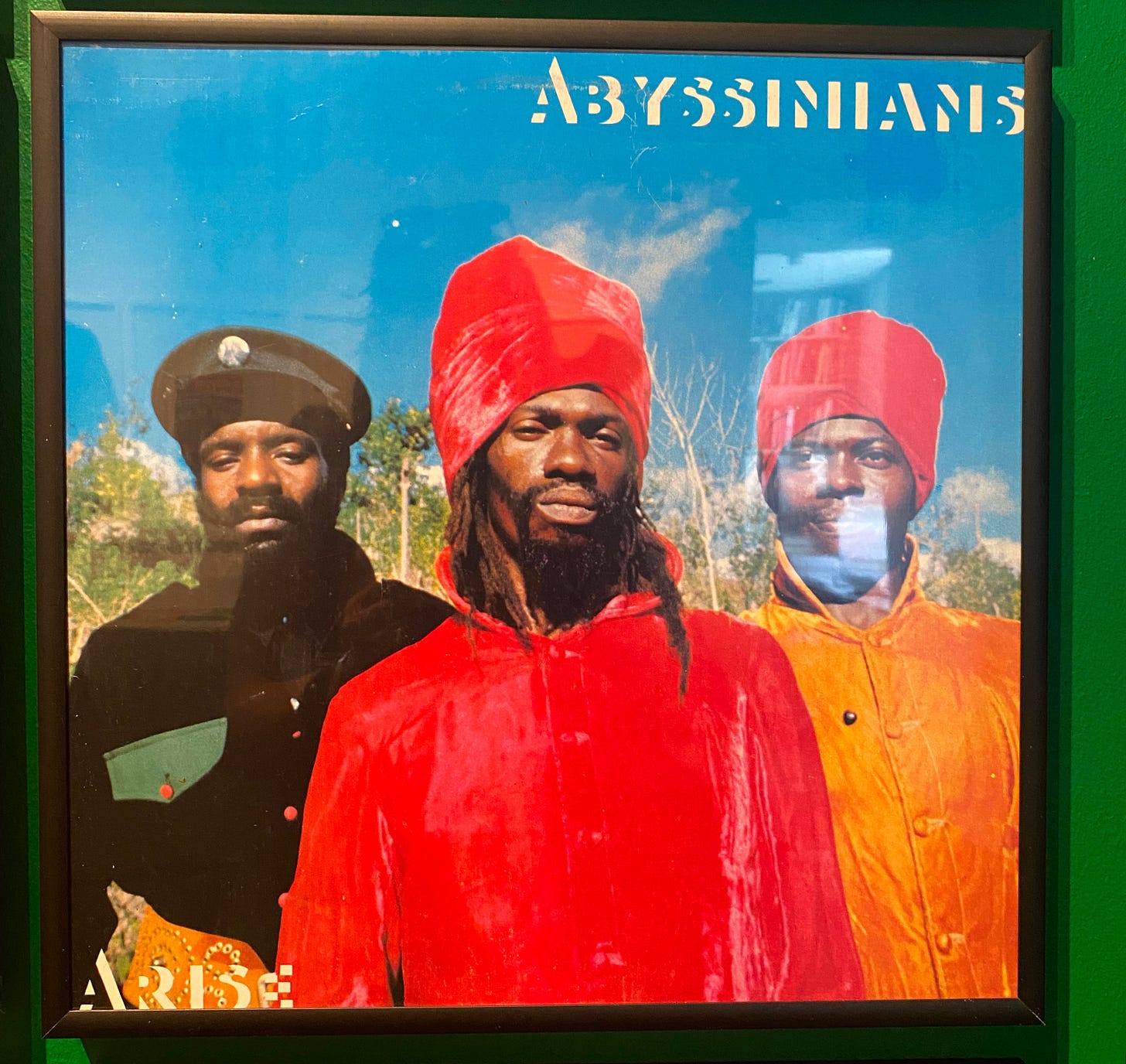

You’ll likely know Dennis Morris from those iconic shots. Johnny Rotten’s wide-lens snarls, Bob Marley wreathed in smoke. But it’s his documentary work photographing working-class London communities, and designing brilliant album covers for reggae artists from the Abyssinians to Lee Perry, that reminds me what an essential chronicler of our culture he truly is.

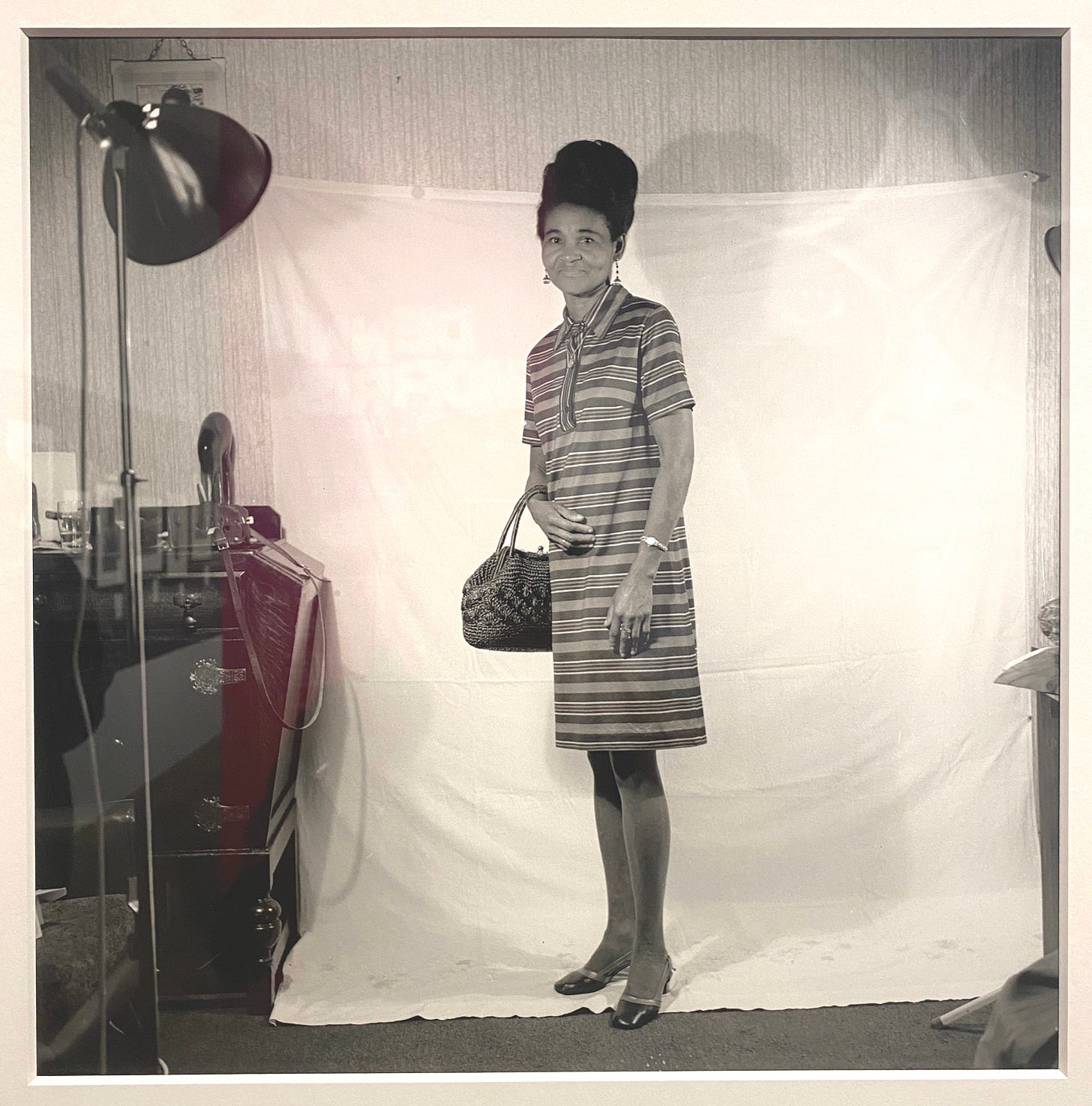

Morris began photography through a camera club at his local church, St Mark’s in Dalston. His first commercial studio was in the bedsit he shared with his mum where he used a white sheet pinned up and a borrowed tungsten light from St Mark’s. He was still a teenager when he created the images that would define his career.

The celebrity photos tend to overshadow the earlier works, but I urge you to seek them out. For those who weren’t part of the Rasta movement or the African and Caribbean working class communities of the time, these images capture not only our sense of cohesion, but also the isolation we felt from the world beyond our front doors.

The energy of Morris’s album covers stands in sharp contrast to his earlier documentary work. They portray subjects exuding an assertive “we’re here” presence and a bold self-assurance that opposed our own experience growing up in the UK. We had internalised our parents’ “good immigrant” ideals of social compliance, a model of behaviour we instinctively recognised as a construct designed to keep us apart. Du Bois’s idea of the “second self” came to mind as I recognised my dad’s face in the expressions of some of Morris’s subjects. His controversial publicity photo of Steel Pulse dressed as Ku Klux Klan members for the sleeve of their 1978 single, was a fearless confrontation, exemplifying the radical messaging these covers carried.

The most touching images for me were the home studio shots from 1970s Dalston. A young teen at the time, Morris was part of a lineage of resourceful photographers who understood that commercial portraiture could also be an act of community service. The importance of that service can’t be overstated. With the cost of printing personal film, many families would otherwise have gone without portraits of their loved ones.

This tradition echoes the great African studio photographers of the 1950s and 60s—masters like Seydou Keïta in Bamako, Malick Sidibé with his portraits of Malian youth, and James Barnor in Accra, who similarly crafted dignified images of their communities through inventive improvisation and a deep understanding of how their subjects wished to be seen.

Morris’s journey from that makeshift Dalston studio to becoming art director at Island Records just a few years later speaks volumes about his talent. At Island, he became the visual architect of the label and helped shape its identity, not only through design but also by signing acts like The Slits and Linton Kwesi Johnson. His work appeared everywhere, on Jamaican cigarette packets, book covers, and band merch, places where images live and breath far from gallery walls.

This show needs more visibility. Go. And don’t assume you know what you’ll find.

Dennis Morris ‘Music + Life’ at The Photographers’ Gallery in London runs through to Sept 28, 2025.