I’m thrilled to welcome Oluwatobiloba Ajayi to our contributor series. As the Noah Davis retrospective at the Barbican enters its final day, Ajayi offers a meditation on the exhibition's significance. With a keen architectural sensibility, Ajayi explores how Davis challenges our understanding of Black spaces and community—revealing how the artist wasn't just painting scenes but building worlds that reimagine physical spaces as sites of communal vitality.

Ajayi illuminates the connections between Davis' paintings and a broader lineage of Black spatial resistance, highlighting the artist's dual role as both painter and community architect through the Underground Museum. Her thoughtful perspective invites us to reconsider the power of space and place in art, a fitting tribute as we reflect on this exhibition.

Please consider supporting Shade Art Review with a subscription. As a reader-supported publication, I share 50% of all subscription income directly with my contributors.

If you're unable to subscribe for 83p weekly, please like and share this writer's work to help it reach a wider audience. Shade Art Review takes hours of dedication to produce, and while we deeply appreciate your emails of support, financial contributions make it possible for us to continue publishing thoughtful criticism like Ajayi's piece.

Your subscription makes a real difference in sustaining independent art writing and fairly compensating our contributors. Thank you for supporting our community of writers.

Enjoy today’s piece and thank you, as always for being here.

Lou.

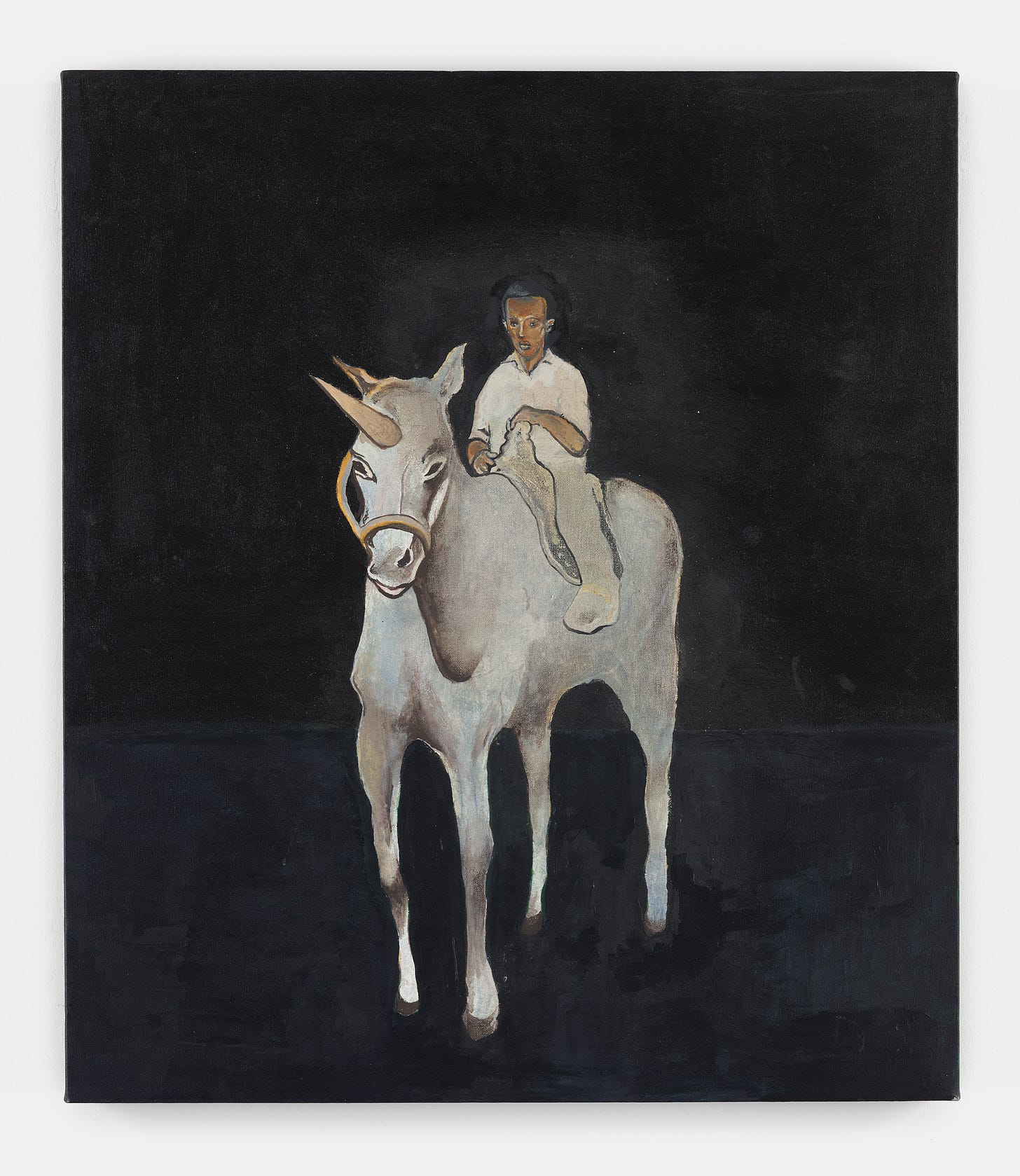

One of the first works you encounter in Noah Davis’ retrospective at the Barbican is 40 Acres and a Unicorn, painted by the late artist in 2007. Within it, a singular figure sits on a unicorn, engulfed by a ground of Black softened by varying textures. It is an unexpected introduction, because its stylistic choices are mostly anomalous to Davis’ typical treatment of figures in communal activity: sleeping, swimming, dancing, spitballing. Here, a lone figure emerges from an abyss, a thick, immersive Blackness.

Though the painting differs from Davis’ steadfast celebration of collective Black presence, 40 Acres and a Unicorn, with its pointed title, signals the betrayal of a spatial promise that Davis’ body of work comes to resolutely defy. The title references the forty acres and a mule guaranteed to some newly freed enslaved people as part of Special Field Orders, No. 15, a land reparation policy proposed following the American Civil War in 1865. This order, with its assurance of literal grounds from which to remake their lives in the aftermath of slavery, marked a potential step towards the ideal of Black emancipation. However, the order was never fully realised. After Abraham Lincoln’s death, it was revoked by Andrew Johnson’s administration. The floated idea of sovereign possession of property became a way to provide—and ultimately deny—agency. This capacity of architecture to shape social reality was fully understood by Davis. His interest in recasting space, imagining it better, and building realms for congregation is evident not only in his canvases but also in his founding of the Underground Museum, which has fortunately continued to find afterlives in the wake of his untimely death.

In most of Davis’ paintings, people are never quite alone. In Isis (2009), a female figure stands with her arms out wide, holding up a skirt she has fanned up and around herself, the searing yellow surface both protecting and boasting of her. She’s framed from above by mottled, draping tree branches that crawl over her clapboard home. To her right, an AC seems to have dislodged from a window, in its place a shadowy figure is barely visible from within the home. She shares her privacy with another. The scene is resplendent; the woman stuns in garments that defy easy definition, existing in quiet rapture with her companion, yet her modest surroundings suggest she is the maker of her magic. There lies the artist’s own alchemy: his ability to inject day-to-day scenes with a sense of gravity, while never taking them too far from their habitual contexts. In other works, a mother bends her child over her knee for a spanking in the privacy of her home; young people gather in entry ways—their slender slackened figures mirroring the verticality of the doorframes; and swimmers congregate at an outdoor pool, where a chain-link fence allows a view through to the residential building overlooking the slick bodies. Davis paints the (Black) quotidian, and architecture is an incessant, inescapable backdrop—the stage from which we perform ourselves.

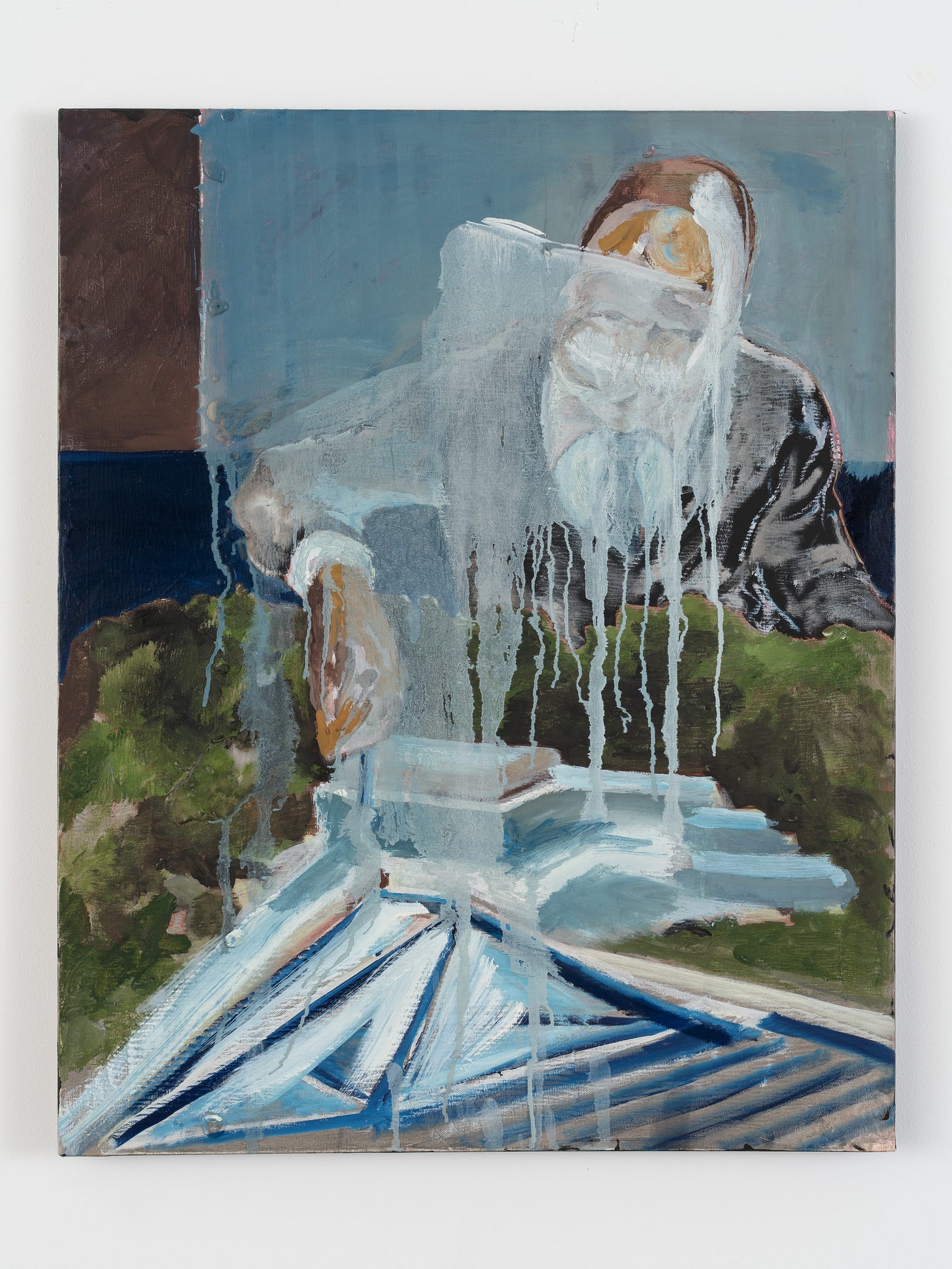

Nowhere is this more evident than in two of Davis’ paintings—The Architect (2009) and The Missing Link 4 (2013). Davis was notably interested in “instances where Black aesthetics and modernist aesthetics collide,” and in his painting of architect Paul Revere Williams, the modernist is Black. Curiously, The Architect is when Davis’ renderings of architecture are at their loosest. In the painting, modernism’s horizontality is alluded to in broad strokes of grey, pale blue, and titanium white, expressing a sense of volume without concrete detail. The architect’s face is also obscured, first in its noncommittal likeness, and doubly in a veil of white dripping paint. Williams, the painting’s subject, was a prolific LA-based architect of the early 1920s and the first Black certified architect west of the Mississippi in 1921. The architect worked across the public and private spheres, designing homes for Frank Sinatra and Lucille Ball, the Beverly Hills Hotel, and the LAX Theme Building.

Despite his professional acclaim, Williams often designed spaces he could not legally occupy. He could enter the Beverly Hills Hotel as an architect but not as a Black person, and most of the homes he designed were on parcels of land Black people could not purchase due to racially restrictive covenants. Alongside his success, Williams’ career is demonstrative of the lethal sphere of consequence echoed by the failed promise evoked in Davis’ 40 Acres painting. If the revocation of Special Field Orders, No. 15 decreed that Black people had no right to the property on which they were forced to labour, Williams' professional circumstances were another spatial symptom of decades of racial dispossession. Again, Black people are tasked with building worlds they can’t move through freely. Yet Davis offers Williams a kind of metaphysical reprieve. The artist obscures Williams’ image, and in turn, the figure of the architect. The role is made symbolic, it is unclear whether it is an act of reverence—a form of aniconism—or a blurring that allows any figure to step into the shoes of the architect, perhaps giving the artist himself free reign to take on the role.

In seeking to theorise what a Black feminist critic of architecture might look like, I am drawn to creative practices as alternative sites of architectural knowledge. My research engages artists such as Amanda Williams, Veronica Ryan, Julie Mehretu, and Barbara Chase-Riboud, as well as the literary manipulations of Dionne Brand, June Jordan, and Christina Sharpe, to name a few. These artists and writers adapt architectural forms, spatial thinking, or tactics of monumentalisation to counter or syncopate the persistence of racial violence. Davis’ paintings—and his work with the Underground—contribute to the richness of this lineage I am tracing. His life’s work offers not only a visual language, but a spatial ethic that contends directly with the unkept promises of liberation.

The trouble with instances where Blackness and modernism collide is that Modernism—at least in its canonical European formulation—is dependent on an invisible (Black) labour, a labour of empire, that allows it to push towards an illusory ideal. In the postwar period, modernist urban planning was complicit in slum clearance under the guise of ‘urban renewal’. In The Missing Link 4, Davis confronts this aporia, painting Mies van der Rohe’s Lafayette Park in Downtown Detroit, a project that razed the predominantly Black neighbourhood of Black Bottom in order to be built. In Missing Link 4, the high-rise apartments form most of the composition. Davis uses a soft grid, chequered with muted blues, browns, and grays, to evoke the matrix of exposed steel and tinted glass of the building. In the foreground, an outdoor pool and its deckchairs are dotted by brown bodies languid and lounging, the dripping, gestural marks of the water a relief against the rectilinear pattern of the apartment. In Davis’ fashioned world, the violence of modernism does not interrupt the practice of Black leisure. Missing Link 4 shows the fecundity of Black life amidst the persistent threat of erasure. Despite the space given to the modernist apartment, the artist’s focus is never exclusively on the building itself, but the moments where an imagined public meets a potential private and the vitality that spills forth from these cusps.

Across his paintings, Davis is quick to include the pavement, a wired fence, a pool’s edge, or trees that line the sidewalks. These are thresholds where people pause to linger, and he recognises that life is made as much in these places as anywhere else. The artist understands architecture as fundamentally communal; he paints it across shifting scales and fluctuating intimacies, illustrating the necessity of the built environment in the construction of social meaning. Like Davis, other artists, writers, and voices outside architecture have long searched for ways to engage the discipline’s power to shape and radically alter space. In the ‘60s, June Jordan collaborated with R. Buckminster Fuller to imagine a utopian housing scheme for Harlem. The pair devised a series of conical towers grafted onto existing apartment buildings, allowing residents to transition upwards rather than uproot their lives in the pursuit of better accommodations. It was a plan to transform Harlem without displacing any of its residents, a virtuous feat, given most ‘urban renewal’ projects, like Lafayette Park, were dependent on the expulsion of existing residents. Despite Jordan’s best intentions, her and Fuller’s plans never moved beyond the proposal. Still, it stands in a lineage of spatial counter-imaginations of which the Underground Museum, founded by Davis and his wife Karon in 2012, is one that made it off the page. The museum opened in Arlington Heights, a working-class Black and Latino neighbourhood, and would go on to host artists such as Kara Walker, Henry Taylor, Lorna Simpson, and Theaster Gates. The UM was a total extension of the life force Noah brought to his paintings, a magnanimous demonstration of his work in presenting Black art on its own terms, to its own people, and building Black spaces resistant to erasure. So while Noah Davis was an artist—one of my dearest—he was also a curator, an architect of sorts, a community steward, and a world-builder.

One of the final bodies of work in the Barbican exhibition is Davis’ Pueblo del Rio series, a painted redress of the housing project, of which Williams was chief architect, originally built to provide affordable housing but eventually devolved to a site of poverty and crime. In Davis’ retelling, he dreams up scenes of jubilation across Pueblo del Rio. Residents gather, their bodies arranged alongside the low-rise buildings in dancerly processions; a grand piano has made its way onto the street; solitary locals perch beneath trees to read or share music from a trumpet gestured towards the street. These are scenes of tender orchestration, an imagined community in unhurried cohesion. In a film at the close of the exhibition, Davis says he wanted to make work that was “extremely normal,” but not “stuck in reality.” His words are prescient. Davis takes the quotidian to its extreme, affirming our day-to-day spaces as sites of fruitful, restorative possibility. Though 40 Acres initiates the exhibition, Davis quickly moves past the singularity of loss. His paintings dwell instead on how Black communities live in excess of structural denial, how we feed and sustain ourselves to surpass our given realities. Although Davis at times cites histories of injury, expulsion, and deprivation, they are the diving board from which his subjects leap forth and fly, unhindered by the inaptitude of systemic contracts to meet the needs of Black people. At the exhibition’s close, like the man seated on the unicorn, we emerge from a ground ripe with potential, yet undefined, eager to make concrete the promise of a freedom found in space.

While we have all the paintings of Noah Davis we will ever have, his work continues to be lived. There was a particular animation felt at the opening as people gathered to share in it, but it remained on my every return. A shared sentience lingered—sustained by the work’s ability to move people, and by that movement’s total insistence on being felt.

Noah Davis showed at Barbican Art Gallery from 6 Feb to 11 May 2025. The exhibition will tour to the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles 8 Jun – 31 Aug 2025 and the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 2026.

Oluwatobiloba Ajayi is a London-based artist and writer.